Robert M. Sanford, Joseph K. Staples, & Sarah A. Snowman

Introduction

Environmental science is a broad, interdisciplinary field integrating aspects of biology, chemistry, earth science, geology, and social sciences. Both holistic and reductionist, environmental science plays an increasing role in inquiry into the world around us and in efforts to manage society and promote sustainability. Mastery of basic science concepts and reasoning are therefore necessary for students to understand the interactions of different components in an environmental system.

How do we identify and assess the learning that occurs in introductory environmental science courses? How do we determine whether students understand the concept of biogeochemical cycling (or “nutrient cycling”) and know how to analyze it scientifically? Assessment of environmental science learning can be achieved through the use of pre- and post-testing, but of what type and nature?

Physics, chemistry, biology, and other disciplines have standardized pre- and post-tests, for example Energy Concept Inventory, Energy Concept Surveys; Force Concept Inventory (Hestenes et al. 1992); the Geoscience Content Inventory (Libarkin and Anderson 2005); the Mechanics Baseline Test; Biology Attitudes, Skills, & Knowledge Survey (BASKS); and the Chemistry Concept Inventory (Banta et al. 1996; Walvoord and Anderson 1998). Broad science knowledge assessments also exist, notably the Views About Science Survey (Haloun and Hestenes 1998). Some academic institutions have developed their own general science literacy assessment tool for incoming freshmen (e.g., the University of Pennsylvania [Waldron et al. 2001]). The literature abounds with information on science literacy. The American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) and the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA) are leaders in developing benchmarks for scientific literacy (AAAS 1993; www.NSTA.org).

Perhaps the closest standardized testing instrument for environmental science is the Student Ecology Assessment (SEA). Lisowski and Disinger (1991) use SEA to focus on ecology concepts. The SEA consists of 40 items in eight concept clusters; items progress from concrete to abstract, from familiar to unfamiliar, and from fact-based (simple recall) to higher-order thinking questions. Although developed principally for testing understanding of trophic ecology (plant-animal feeding relationships), this instrument can be used in most ecology or environmental science classes, even though it does not address all aspects of environmental science (for example, earth science, waste management, public policy).

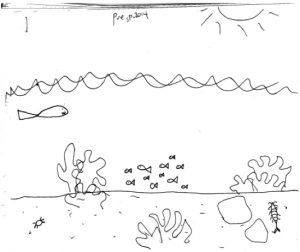

FIGURE 1. A representative ecosystem drawing from the first day of class.

The Environmental Literacy Council provides an on-line test bank that can be used for assessment (http://www.enviroliteracy.org/article.php/580.html). Results of this and other instruments suggest that the average person’s environmental knowledge is not as strong as he or she thinks (Robinson and Crowther 2001). Environmental knowledge assessment may help us to determine what additional learning needs to be done in creating an environmentally literate citizenry—an important public policy task (Bowers 1996). However, a major reason for assessing environmental knowledge is to improve teaching. If we can assess how students conceptualize an ecosystem at the start of a course, then we can measure the difference at the end of the course. Additionally, understanding what knowledge they possess at the start of a course will help us expand their knowledge base in a manner tailored to their initial understandings and their needs.

The challenge lies in deriving a rapid assessment tool that will help determine abilities to conceptualize and that also has comparative and predictive value. It is quite common in environmental science courses to ask students to draw an ecosystem—it can be done as an exam question, as homework, or as an in-class project. Virtually all environmental science textbooks contain illustrations of ecosystems. An environmental laboratory manual we frequently use (Wagner and Sanford 2010) asks students to draw an ecosystem diagram as one of the assignments. But what about examining how the students’ drawings illustrate growth in knowledge and understanding—their ability to use knowledge gained and to communicate ecological relationships in a model? We needed an instrument that provided immediate information, could be contained on one page, would not take a lot of class time, and that did not look like a test. The draw-an-ecosystem instrument meets those criteria, but there is a price: the difficulty of quantifying and comparing the drawings. It seemed a worthwhile challenge to work those bugs out, and even if that proved to be impossible, the students themselves could see the increased ecological sophistication of their drawings and would experience positive feedback from the change.

The Draw-an-Ecosystem Approach

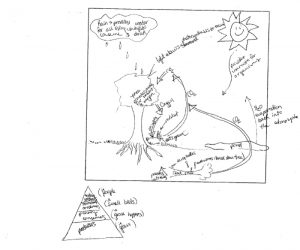

Our approach is to use a pre-test and post-test in which students draw and label an ecosystem, showing interactions, terms, and concepts (Figure 1 and Figure 2). The assignment is open-ended. We hand out a page with a blank square on it and the following directions:

Date_______. Course ________. Please draw an ecosystem in the space below. It can be any ecosystem. Label ecosystem processes and concepts in your diagram. Take about 15 or 20 minutes. This will not be graded, it isn’t an art assignment, and the results will be kept anonymous.

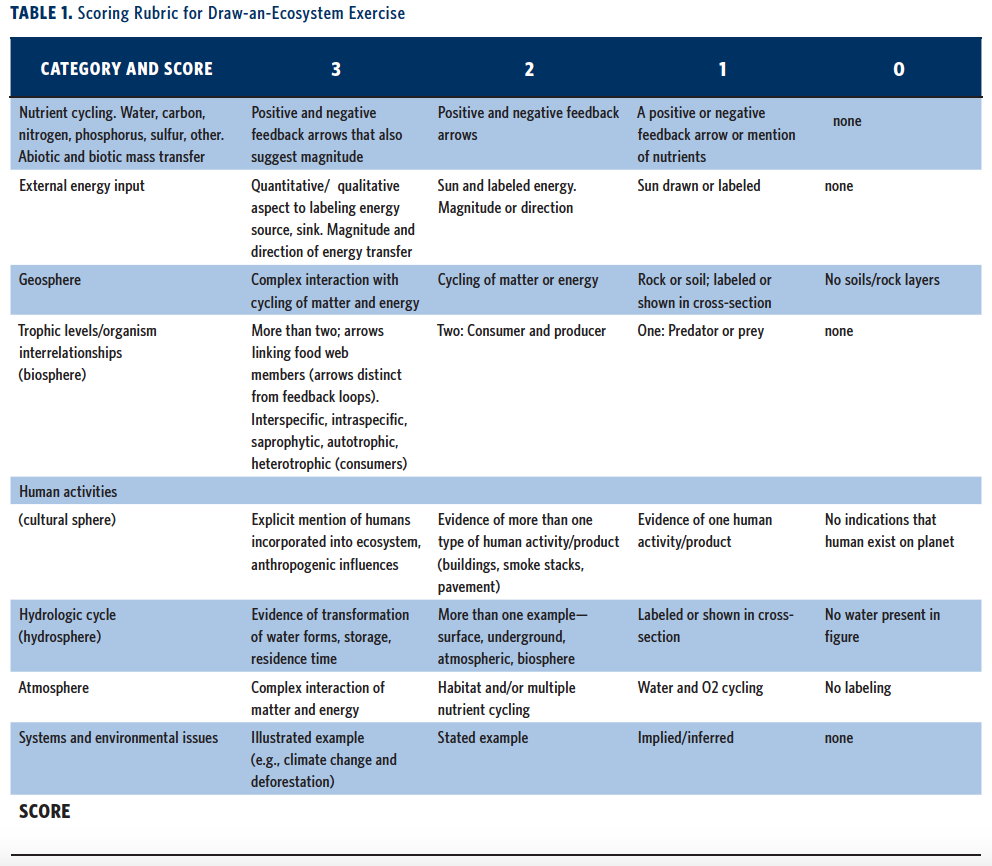

We tried out this assessment in our graduate summer course in environmental science for sixth–eighth grade teachers (even short-term courses can produce a change in environmental knowledge according to Bogner and Wiseman [2004]) and in our Introduction to Environmental Science course. We developed a rubric to evaluate and score the pre- and post-test ecosystem diagrams drawn by students. The rubric included eight categories, each with a 0–3 score, where 0 represented no display of that category and 3 represents a comprehensive response. The categories, labeled A-H, cover ecosystem aspects (listed below). Certainly, not all eight categories are equal, nor should they be equally rated or represented; however, since we are examining pre- and post-course conceptualization of ecosystems, the comparative value of the scoring remains, and we decided it was reasonable to sum the category scores for a final score. Accordingly, the maximum possible score was 24. The scores were then compiled and analyzed to determine whether there was a statistically significant difference in pre- and post-test scoring.

To interpret the student ecosystem diagrams, we examine the following factors:

- Presentation of the different spheres (hydrosphere, atmosphere, biosphere, geosphere, and cultural sphere)

FIGURE 2. Typical drawing of an ecosystem at the end of a semester-long environmental science course.

- Proportional representation of species and communities

- Recognition of multiple forms of habitat and niche

- Biodiversity

- Exotic/invasive species

- Terminology

- Food chain/web

- Recognition of scale (micro through macro)

- Biogeochemical (nutrient) cycles

- Earth system processes

- Energy input and throughput

- Positive and negative feedback mechanisms

- Biological and abiotic interactions and exchanges

- Driving forces for change and stability (dynamics)

Initially we used the above factors as a guide in interpreting the drawings and comparing the pre-test and post-test drawings for each student—we did not compare one student’s work with another. However, if the ecosystem test can become a valid and reliable standardized assessment, then comparison makes sense and will inform how an entire course makes a difference in student learning rather than just the progress of an individual student. Accordingly, we developed a scoring rubric (Table 1).

In determining the categories and weights for each scoring rubric, we consulted three other environmental science faculty with experience in teaching an introductory environmental science course. We sought a scale for which both beginners

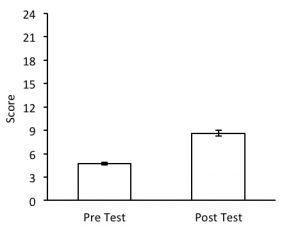

and professionals would achieve measurably distinct scores. To ensure objectivity, we scored multiple examples before settling on the final rubric elements and weights. This is similar to the norming approach used by the College Board in scoring Advanced Placement (AP) Environmental Science exams. The final scores reflect a student’s holistic understanding of ecosystems. The maximum score for the pre- and post-test is the same, 3 points x 8 categories = 24. Analysis of pre- and post-course test scores using a Student’s t-test for independence, with separate variance estimates for pre-test and post-test groups, was conducted using Statistica v.10 (StatSoft, Tulsa, OK). Analysis revealed a significant enhancement of students’ abilities to communicate their understanding of ecological concepts (t = -10.77, df = 364, p < 0.001) (Figure 3). We also tested the scoring system on a small group of workshop participants at the New England Environmental Education Alliance conference (October 2014). Participants included members of their state’s respective environmental education association, plus a mixture of grade school teachers and non-formal educators (with environmental education equivalent to or higher than that achieved by the post-course group of students). The scores by these educators averaged 13 and ranged between 10 and 15.

and professionals would achieve measurably distinct scores. To ensure objectivity, we scored multiple examples before settling on the final rubric elements and weights. This is similar to the norming approach used by the College Board in scoring Advanced Placement (AP) Environmental Science exams. The final scores reflect a student’s holistic understanding of ecosystems. The maximum score for the pre- and post-test is the same, 3 points x 8 categories = 24. Analysis of pre- and post-course test scores using a Student’s t-test for independence, with separate variance estimates for pre-test and post-test groups, was conducted using Statistica v.10 (StatSoft, Tulsa, OK). Analysis revealed a significant enhancement of students’ abilities to communicate their understanding of ecological concepts (t = -10.77, df = 364, p < 0.001) (Figure 3). We also tested the scoring system on a small group of workshop participants at the New England Environmental Education Alliance conference (October 2014). Participants included members of their state’s respective environmental education association, plus a mixture of grade school teachers and non-formal educators (with environmental education equivalent to or higher than that achieved by the post-course group of students). The scores by these educators averaged 13 and ranged between 10 and 15.

Discussion

FIGURE 3. Draw-an-Ecosystem Rubric Test Scores. Average test scores with SE (bars) for freshmen/transfer undergraduate students in first-semester Environmental Science. Pre-test (n =297, mean = 4.7) and Post-test (n =60, mean = 8.6).

The draw-an-ecosystem test provides an open-ended but structure-bounded means to gauge a person’s understanding about ecosystems. We measured change between the first week of a semester-long environmental science course (four credits of lecture and lab) and the last week. The change showed an approximate doubling of scores. The drawings provide clues to where the students are for their starting points and provide a way to indicate possible misconceptions about science or the environment—misconceptions that may need to be cleared up for proper learning. Thus, the drawings can be a useful diagnostic tool for both the student and the teacher. They may also give insight into geographical, cultural, or social biases. For example, many ecosystem drawings were of ponds, not surprising given the water-rich environment of Maine. None of the over 300 drawings were of desert ecosystems, yet such might be conceptually more common for people from an arid region such as the Southwest. Another aspect of the sample ecosystem drawings is that they tend to be common rather than exotic, leading one to wonder whether we care for what we do not know, or if perhaps the opposite is true—a “familiarity breeds contempt” scenario in which the vernacular environment is seen as less important due to its commonality. A related question is whether or not the ecosystems selected for portrayal change as a result of education. Not only might students think more deeply about ecosystems, but perhaps they are more aware of and value the greater variety of them.

Another benefit of the ecosystem drawing is that it adds another dimension to the learning process. It provides a different way of assimilating and processing information, although according to our sample, artists tend to score about the same as those with fewer artistic skills, suggesting that perhaps a drawing assignment validates their supposedly lesser artistic abilities. Certainly, an exercise that incorporates multiple modes of representation, expression, and engagement—such as drawing and writing—fits better with a Universal Design for Learning (UDL) approach; these modes are the three principles of UDL (Burgstahler and Cory 2008; Rose et al. 2005).

In the future, we may seek a way to reduce the large number of categories in the scoring system, especially if the test is to be used with younger age groups. We should also attain a more comprehensive method of assessing inter-rater agreement for scoring the drawings. We may also explore use of the ecosystem drawings as discussion starters for peer evaluation and collaborative learning. Ecosystem concepts seem to be a powerful way of capturing and reflecting student thinking about environmental settings as dynamic systems.

Acknowledgements

Maine Mathematics and Science Teaching Excellence Collaborative (MMSTEC), an NSF-funded program, inspired the initial idea of this paper. Professors Jeff Beaudry, Sarah Darhower, Bob Kuech, Travis Wagner, and Karen Wilson provided insight.

About the Authors

Robert M. Sanford is Professor and Chair of Environmental Science and Policy at the University of Southern Maine. He is a SENCER Fellow and a co-director of SCI New England.

Robert M. Sanford is Professor and Chair of Environmental Science and Policy at the University of Southern Maine. He is a SENCER Fellow and a co-director of SCI New England.

Joseph K. Staples teaches in the Department of Environmental Science and Policy at the University of Southern Maine. He was recently appointed a SENCER Fellow.

Joseph K. Staples teaches in the Department of Environmental Science and Policy at the University of Southern Maine. He was recently appointed a SENCER Fellow.

Sarah A. Snowman works at L.L. Bean and is a recent graduate of the University of Southern Maine, where she majored in Business and minored in Environmental Sustainability.

Sarah A. Snowman works at L.L. Bean and is a recent graduate of the University of Southern Maine, where she majored in Business and minored in Environmental Sustainability.

References

American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). 1993. Benchmarks for Scientific Literacy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Banta, T.W., J.P. Lund, K.E. Black, and Frances W. Oblander, eds. 1996. Assessment in Practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Bogner, F.X., and M. Wiseman. 2004. “Outdoor Ecology Education and Pupils’ Environmental Perception in Preservation and Utilization.” Science Education International 15 (1): 27–48.

Bowers, C.A. 1996. “The Cultural Dimensions of Ecological Literacy.” Journal of Environmental Education 27 (2): 5–11.

Burgstahler, S.E., and R.C. Cory. 2008. Universal Design in Higher Education: From Principles to Practice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Environmental Literacy Council. Environmental Science Testbank. http://www.enviroliteracy.org/article.php/580.html (accessed November 30, 2016).

Halloun, I., and D. Hestenes. 1998. “Interpreting VASS Dimensions and Profiles for Physics Students.” Science and Education 7 (6): 553–577.

Hestenes, D., M. Wells, and G. Swackhamer. 1992. “Force Concept Inventory.” The Physics Teacher 30: 141–158.

Libarkin, J.C., and S.W. Anderson. 2005. “Assessment of Learning in Entry-Level Geoscience Courses: Results from the Geoscience Concept Inventory.” Journal of Geoscience Education 53: 394–201.

Lisowski, M., and J.F. Disinger. 1991. “The Effect of Field-Based Instruction on Student Understandings of Ecological Concepts.” The Journal of Environmental Education 23 (1): 19–23.

Nuhfer, E.B., and D. Knipp. 2006. “The Use of a Knowledge Survey as an Indicator of Student Learning in an Introductory Biology Course.” Life Science Education 5 (4): 313–314.

Robinson, M., and D. Crowther. 2001. “Environmental Science Literacy in Science Education, Biology & Chemistry Majors.” The American Biology Teacher 63 (1):9–14.

Rose, D.H., A. Meyer, and C. Hitchcock, eds. 2005. The Universally Designed Classroom: Accessible Curriculum and Digital Technologies. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Maine Mathematics and Science Teaching Excellence Collaborative (MMSTEC). http://mmstec.umemat.maine.edu/MMSTEC/

Sexton, J.M., M. Viney, N. Kellogg, and P. Kennedy. 2005. “Alternative Assessment Method to Evaluate Middle and High School Teachers’ Understanding of Ecosystems.” Poster presented at the international conference for the Association for Education of Teachers in Science, Colorado Springs, CO.

Wagner, T., and R. Sanford. 2010. Environmental Science: Active Learning Laboratories and Applied Problem Sets. 2nd ed. New York: Wiley & Sons.

Waldron, I., K. Peterman, and P. Allison. 2001. Science Survey for Evaluating Scientific Literacy at the University Level. University of Pennsylvania. (http://www.sas.upenn.edu/faculty/Teaching_Resources/home/sci_literacy_survey.html).

Walvoord, B.E., and V.J. Anderson. 1998. Effective Grading: A Tool for Learning and Assessment. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Current Issue

- Research Article

Students as Partners in Curricular Design: Creation of Student-Generated Calculus Projects

Steve Cohen, Melanie Pivarski, & Bárbara González-Arévalo

- Project Report

A Research Project in Inorganic Chemistry on the Flint Water Crisis

Stephen G. Prilliman

- Project Report

Geek Sneaks: Incorporating Science Education into the Moviegoing Experience

Dan Mushalko, Johnny DiLoretto, Katherine R. O’Brien, & Robert E. Pyatt

Mission Statement

The mission of this journal is to explore constructive connections between science education and civic engagement that will enhance both experiences for our students. In the 21st century, mathematical and scientific reasoning is an essential element for full participation in a democratic society. Contributions to this journal will focus on using unsolved, complex civic issues as a framework to develop students’ understanding of the role of scientific knowledge in personal and public decision making, along with examining how such knowledge is embedded in a broader social and political context. Since many pressing issues are not constrained by national borders, we encourage perspectives that are international or global in scope. In addition to examining what students learn, we will also explore how this learning takes place and how it can be evaluated, documented, and strengthened. By exploring civic questions as unsolved challenges, we seek to empower students as engaged participants in their learning on campus and as citizens in their communities.

Publishing the Journal

The Journal is published twice per year in an online format. The official publisher of the journal is The Department of Technology and Society at Stony Brook University, home of the National Center for Science and Civic Engagement. Editorial offices for the Journal are located in Lancaster, PA at Franklin & Marshall College.

Editorial Board

Publisher:

Wm. David Burns, National Center for Science and Civic Engagement

david.burns@sencer.net

Co-Editors in Chief:

Trace Jordan, New York University, U.S.A.

trace.jordan@nyu.edu

Eliza Reilly, NCSCE, U.S.A.

eliza.reilly@stonybrook.edu

Managing Editor:

Marcy Dubroff, The POGIL Project, U.S.A.

marcy.dubroff@fandm.edu

Editorial Board Members:

Sherryl Broverman, Duke University, U.S.A.

sbrover@duke.edu

Shree Dhawale, Indiana University – Purdue University Fort Wayne, U.S.A.

dhawale@ipfw.edu

David Ferguson, Stony Brook University, U.S.A.

dferguson@notes.cc.sunysb.edu

Matthew Fisher, St. Vincent College, U.S.A.

matt.fisher@email.stvincent.edu

Robert Franco, Kapiolani Community College, U.S.A.

bfranco@hawaii.edu

Ellen Goldey, Wofford College, U.S.A.

goldeyes@wofford.edu

Nana Japaridze, I. Beritashvili Institute of Physiology, Republic of Georgia

nadia_japaridze@yahoo.com

Cindy Kaus, Metropolitan State University, U.S.A.

cindy.kaus@metrostate.edu

Theo Koupelis, Broward College, U.S.A.

tkoupeli@broward.edu

Jay Labov, National Research Council, U.S.A.

jlabov@nas.edu

Debra Meyer, University of Johannesburg, Republic of South Africa

debra.meyer@up.ac.za

Kirk Miller, Franklin & Marshall College, U.S.A.

kirk.miller@fandm.edu

Amy Shachter, Santa Clara University, U.S.A.

ashachter@scu.edu

Garon Smith, University of Montana, U.S.A.

garon.smith@umontana.edu

View editorial board member biosketches.

Submission Guidelines

View the submission guidelines.

Archives